King's Road

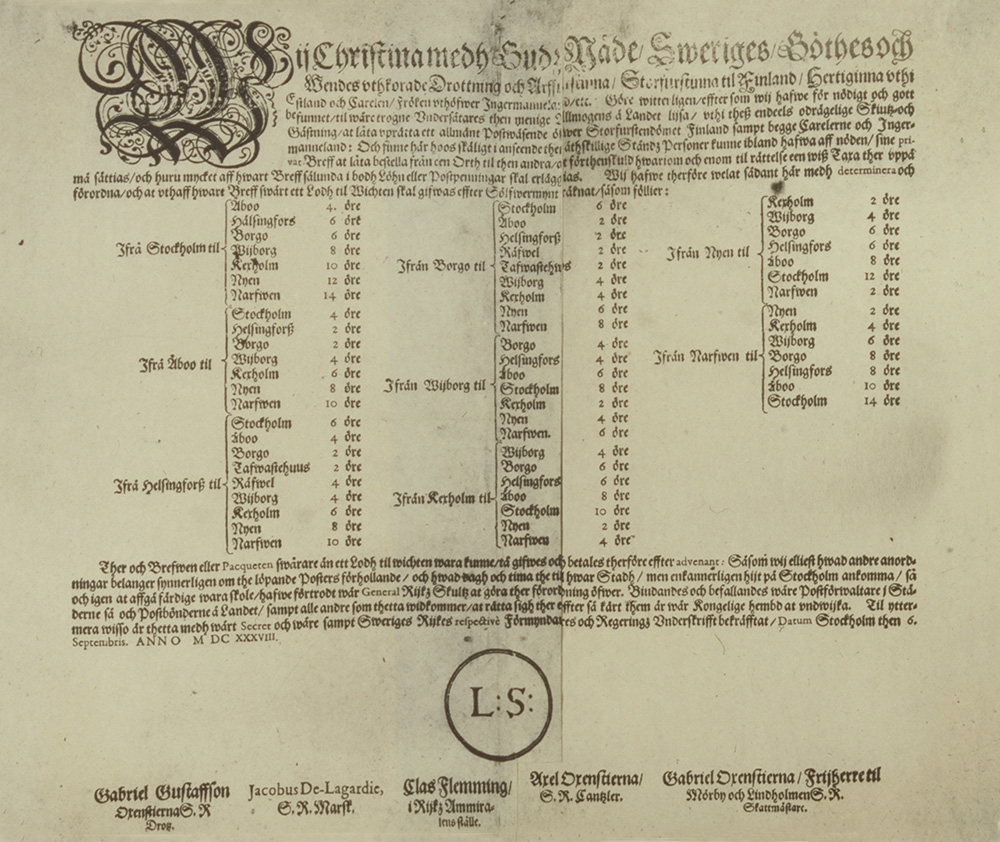

Sweden started to emerge as a great power around the Baltic Sea in the mid-16th century. Ruling the vast kingdom required close communications between the regions, which was the reason the crown established the postal services. The first ordinance concerning mail delivery was issued on 20 February 1636, and it remained in force in Sweden and Finland for the following centuries.

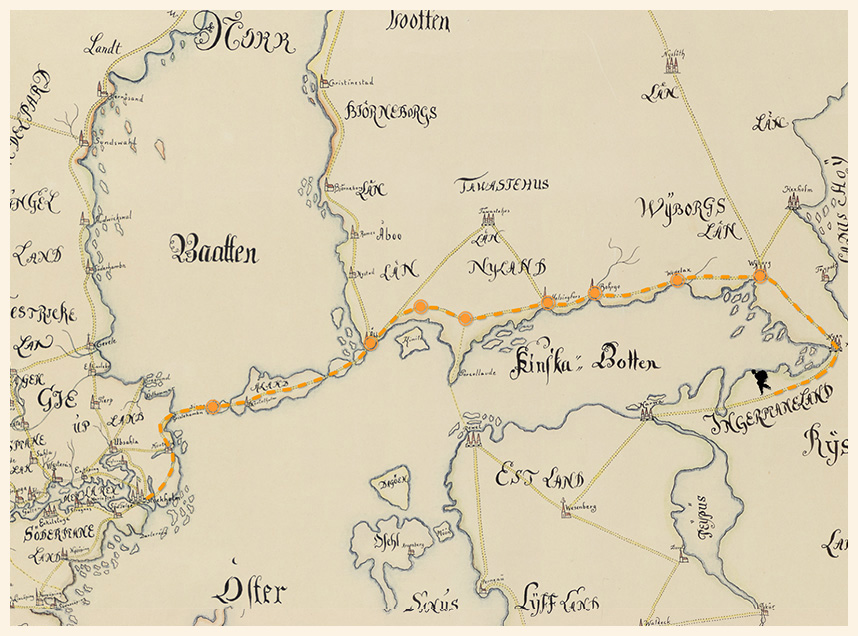

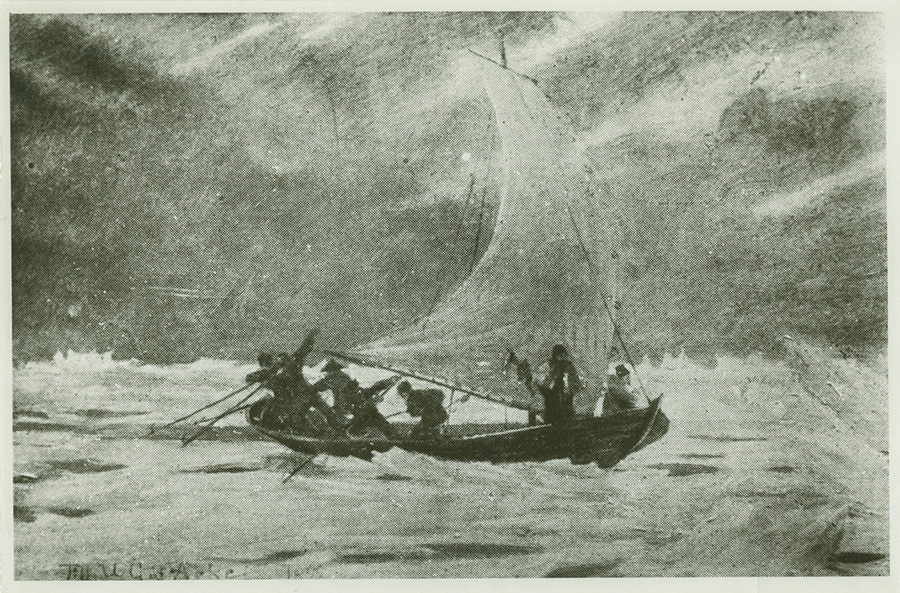

The first mail route to the east ran from Stockholm via the Sea of Åland to Turku, and along the south coast of Finland to Narva in Estonia, which was a politically critical location. The mail routes in Finland extended into the Baltic countries. The route was unique in that it covered a 53-kilometre sea voyage across the Sea of Åland in addition to the roads on land.

The service on the route was launched in 1638, which was also the year when the route from Helsinki to Hämeenlinna was opened, followed by the route from Turku to Hämeenlinna the next year. The mail route across the Gulf of Finland was also in use in the early 1640s.