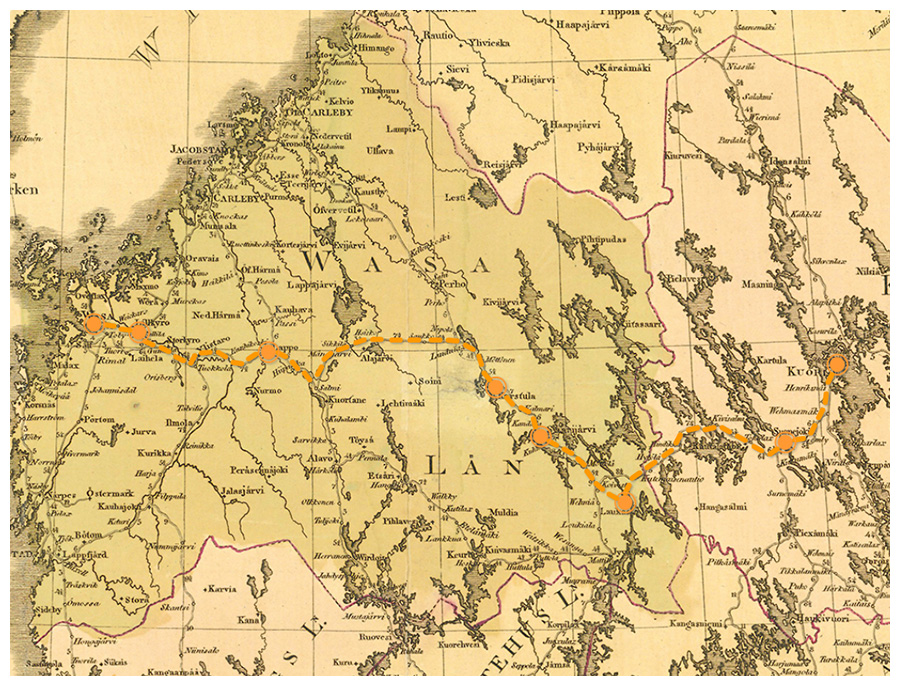

Kuopio–Vaasa Road

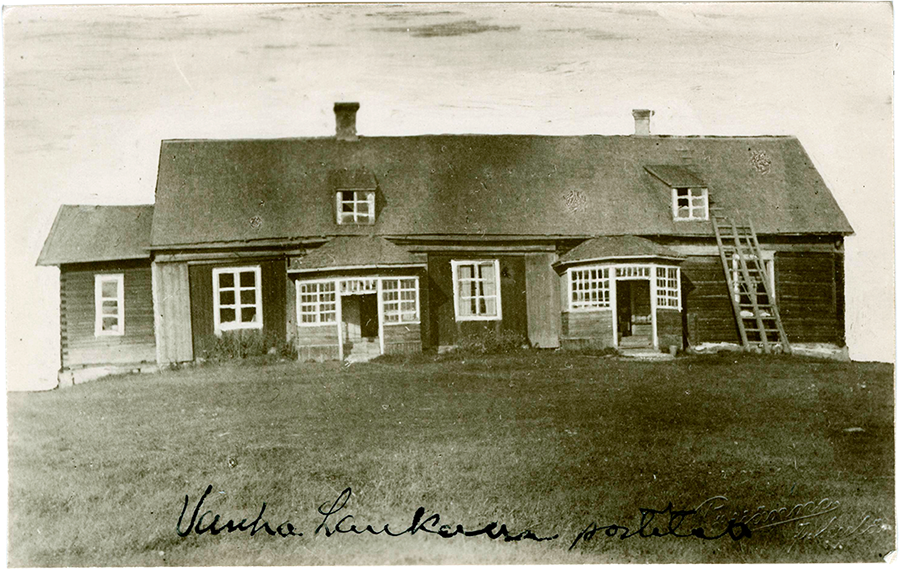

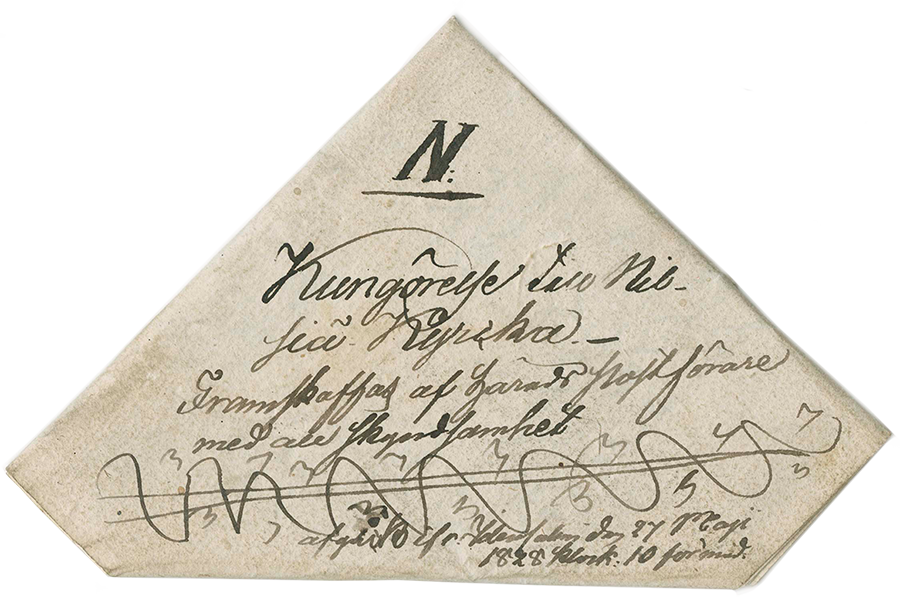

Administration and trade developed in Finland in the late 18th century. In 1776, the province of Kuopio was separated from the province of Kymmenegård, and the Vaasa Court of Appeal was founded. Kuopio, the capital of the province, belonged to the jurisdiction of the Vaasa Court of Appeal. To keep Kuopio and Vaasa connected, a postal line between the two towns was established and a post office was set up in Kuopio in 1776. The post office in Vaasa had already been established in 1645.

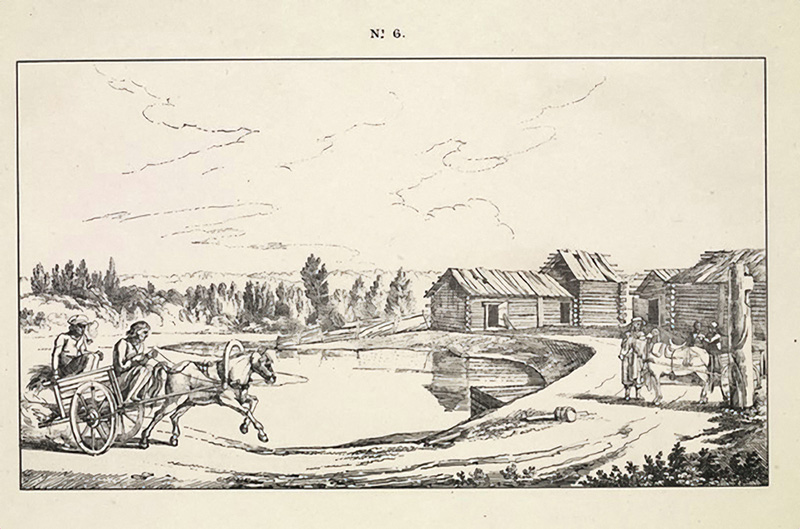

Once the trade ban in the Gulf of Bothnia ended, merchants in Vaasa and Kokkola wanted to buy and sell merchandise from Savo. Because there were no passable roads from the inland areas to the coast, people and goods mainly travelled by water.

A new road was needed to connect the coast and the hinterland for both administrative and financial reasons. The decision to build the Kuopio–Vaasa road was made in 1775, and it was completed in 1784. The road, which connected the northern parts of Savo and Häme to the coastal towns, developed and remained the artery of trade and traffic in Southern Ostrobothnia until the end of the Swedish rule in Finland (1809).