Ostrobothnian

Coastal Road

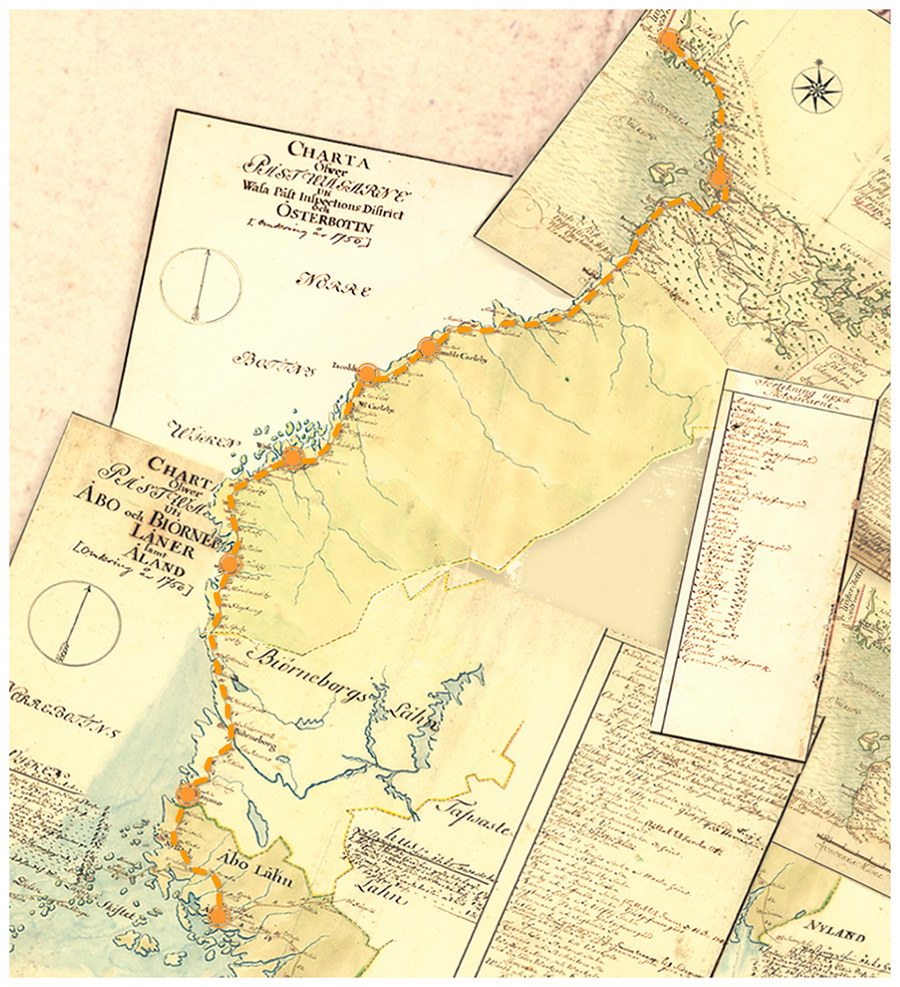

The history of the Ostrobothnian coastal road, which ran north from Turku, is intertwined with Sweden’s foreign policy, wars, trade and communications. The road was built slowly during the 17th and 18th centuries, and it eventually replaced the Kyrönkangas road, which ran inland.

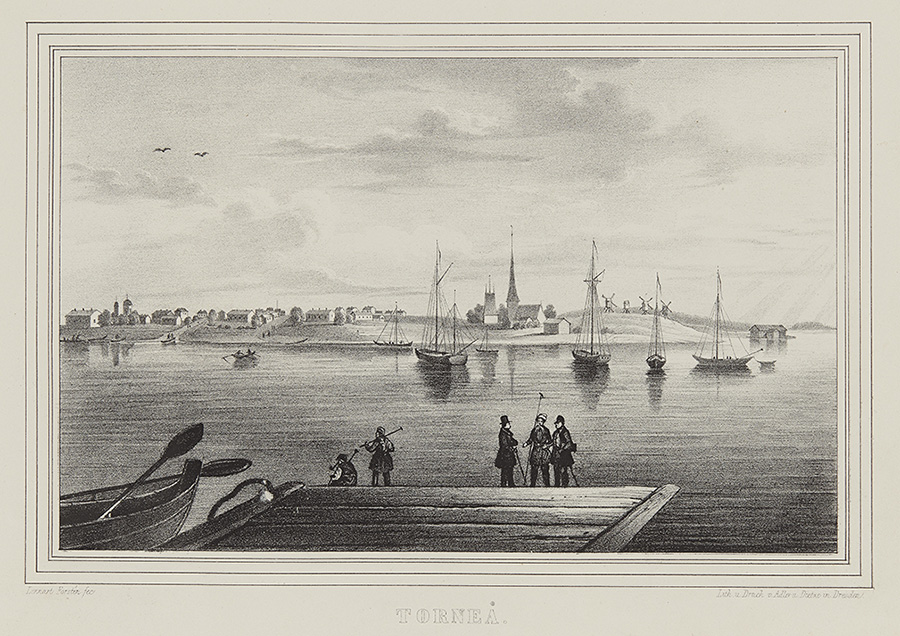

Towns were not allowed to engage in foreign trade before 1765, so the coastal towns turned their attention across the Gulf of Bothnia to Sweden. After the restrictions on trading were lifted, there was a need to set up transport connections between the nearby areas. Ostrobothnia’s coastal road served a wide range of people, including soldiers, postmen and peasants travelling to towns.

The postal services were also an important reason for connecting the towns to each other via the coastal road. Communications in the 18th century meant the information contained in letters delivered by nominated peasant farmers. The king and his officials issued orders and instructions by letters, and his subjects also used the postal services for various purposes. The importance of the coastal road was even clearer during wartime and when the roads were not passable due to frost, as mail could not be delivered by the usual route from Stockholm via the Åland Islands to Turku; instead, letters had to be carried around the Gulf of Bothnia.